Papaver Capsula, Poppy CapsulePost Khashkhash (Unani) |

|

Herbarius latinus, Petri, 1485

Herbarius latinus, Petri, 1485 |

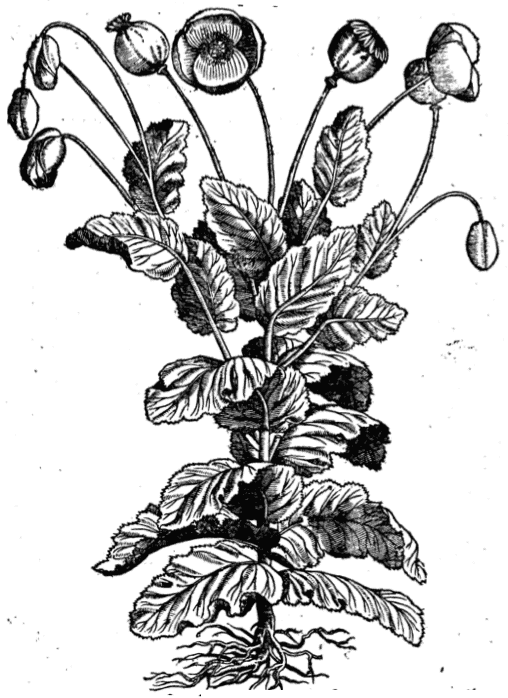

Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491

Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491 |

|

|

|

New Kreuterbuch, Matthiolus, 1563 |

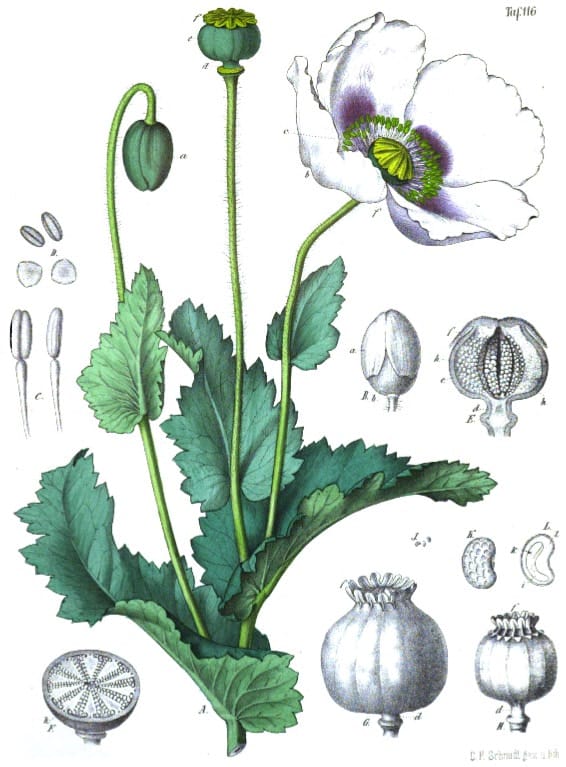

Atlas der officinellen pflanzen, Felix, 1899 |

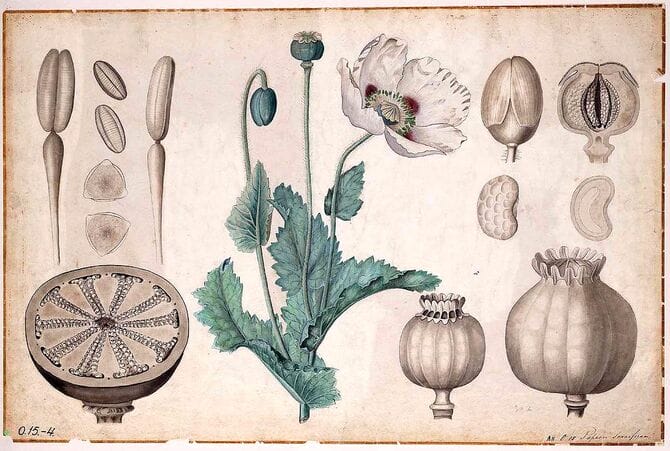

Botanische wandplaten, 1904–1914

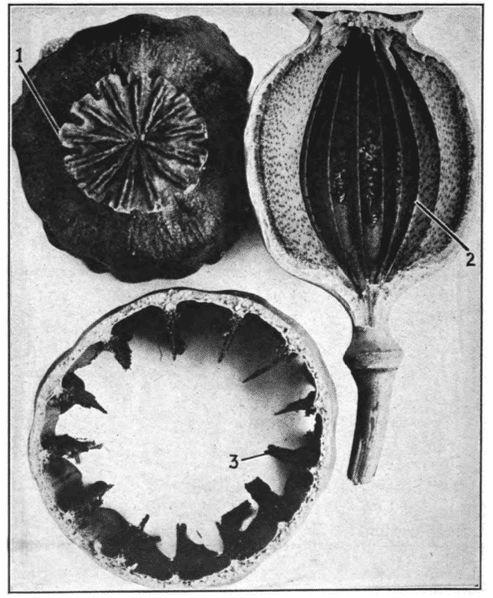

Botanische wandplaten, 1904–1914 POPPY CAPSULE

POPPY CAPSULE1. Yellowish-white spotted placentae. 2. Persistent stigma disk.

3. Cross-section of a fruit.

Squibb’s Atlas of the Official Drugs, Mansfield, 1919

Botanical name:

Papaver spp. P. somniferum is the Opium Poppy

Parts used:

Capsules, Herb, Flowers

See also Opium and Poppy seed

Temperature & Taste:

Cold, dry. Bitter

Classifications:

2I. ANTISPASMODIC. 2R. NARCOTICS & HYPNOTICS

3L. ANTI-TUSSIVE

Uses:

1. Calms the Mind, Stops Pain:

-promote Sleep and rest

-all types of pain

-Externally to ease Pain, cause Sleep when laid to the Head or Feet

-Madness, mania, Irritability

2. Stops Cough, Consolidates the Lungs:

-chiefly for Coughs

-Hoarseness and Consumption

3. Astringes to Stop Leakage:

-Fluxes of the Belly, chronic Diarrhea etc.

-also to help stop Bleeding of the Stomach or Lungs

4. Externally:

-the oil is applied to Heat and Inflammation

Dose:

Dried Capsules in Decoction: 3–9 grams

Dried leaf in Decoction: 6–12 grams

Comment:

As a medicine to reduce pain, calm the mind and nerves, in decending order of strength are: Opium, dried Capsules, dried Leaf, Seed

Substitute:

1. Wild Lettuce extract; “The wild variety of Lettuce resembles Black Poppy in properties.” (Avicenna)

2. Poppy seed

Correctives:

1. Strengthened when used with Vinegar, Prunus Wu Mei and Citrus Ju Pi (Li Shi Zhen)

2. Taken with Si Jun Zi Tang (a formula) will stop it from harming the Stomach.

Preparation:

1. Vinegar-fried Poppy Capsule:

Peel the thin capsule, dry in the shade, then cut into slices, mix with rice vinegar, then stir-fry to dry.

Processed with vinegar moderates its effect and makes it mild and safe. (TCM)

2. Honey-fried Poppy Capsule:

Cut into strips as above, then add a little Honey and stir-fry until the honey is no longer sticky.

This moderates its effect. It is also better for Cough. (TCM)

Main Combinations:

1. Sedative:

i. Poppy with Chicory (Memorial Pharmaceutique, 1824)

ii. Poppy with Lime flower, Orange flower (Ratier)

iii. Lettuce Water, Syrup of Poppy

iv. Orange-flower water, Balm Water, Syrup of Poppy (Ratier)

v. Poppy with Lettuce, Purslane (Memorial Pharmaceutique, 1824)

iv. Lily Water, Orange-flower water, Syrup of Borage, Syrup of Poppy (Memorial Pharmaceutique, 1824)

2. Madness, Poppy with Violet, Water Lily, Rose, Camomile (as in Powder for Madness (2))

3. Cough:

i. Syrup of Poppy, Oil of Almonds (Saunders)

ii. Melon seed, Barley water; form an emulsion and add Syrup of Poppy (Nouveau Formulaire Medicale et Pharmaceutique, 1820)

iii. Poppy heads with Dates, Jujubes, Licorice, Marshmallow, Maidenhair. (Formulaire Magistral et Memorial Pharmaceutique, 1823)

iv. Poppy flowers with flowers of Mullein, Linden, Violet, Coltsfoot, Mallow, Marshmallow (as in Infusion of Seven Flowers)

4. Fomentation for heat and pain:

i. Poppy heads, Camomile, Mullein (Dispensatorium Fuldense, 1791)

ii. Poppy heads, Peppermint, Camomile (Pharmacopoeia medici practici universalis, Bruxelles, 1817)

iii. Poppy heads, Elder flower, Henbane leaf (Pharmacopoeia Herbipolitania, 1796)

iv. Poppy heads, Dill seed, Camomile, Henbane, Black Nightshade, (Dispensatorium medico pharmaceuticum Palatinatus, 1764)

Major Formulas:

Powder for Madness (2) (Rondeletius)

Lohoch of Poppy (Lohoch de Papavere)

Jiu Xian San

Zhen Ren Yang Zang Tang

Cautions:

1. Avoid overdose or long-term usage

2. Not used in acute Diarrhea or Dysentery, and best not used in acute Cough.

Toxicity:

Toxic in excess, severe overdose can result in respiratory paralysis.

Main Preparations used:

Dehydrated Juice of the Leaves, Extracted Juice (‘Opium’), Distilled Water of the Flowers and Heads, Syrup of the Decoction of the Heads and Flowers, Compound Syrup, various Electuaries

1. Syrup of Poppy:

i. Poppy heads with Seeds (8 oz.), Spring Water (4 lbs.). Boil to one-half; allow to sit and settle; add to the strained liquor White Sugar (3 lbs.). Make a Syrup. (Dispensatorium medico pharmaceuticum Palatinatus, 1764)

ii. Dried Poppy heads, seeds removed (14 oz.), Refined Sugar (2 lbs.), Boiling Water (2 1/2 gallons). Macerate the Poppy in the water for 12 hours; boil down gently to one gallon and express strongly; boil the strained liquor to 2 pounds, and strain again while hot. Set aside for 12 hours for the sediment to settle, then reduce to one pint, add the Sugar, and form a syrup. (London)

2. Extract of Poppy:

i. Poppy heads, without seeds (1 pound), Boiling Water (1 gallon). Macerate 24 hours, boil to one-half, then strain hot. Evaporate to a proper consistency in a water-bath. Sedative, narcotic. Dose: 1–2 grains. (Edinborough)

-

Extra Info

-

History

|

‘The medicinal properties of the milky juice of the poppy have been known from a remote period. Theophrastus who lived in the beginning of the 3rd century B.C. was acquainted with the substance in question… The investigations of Unger (1857,) have failed to trace any acquaintance of ancient Egypt with opium. Scribonius Largus in his Compositiones Medicamentorum (circa A.D. 40) notices the method of procuring opium, and points out that the true drug is derived from the capsules, and not from the foliage of the plant. About the year 77 of the same century, Dioscorides plainly distinguished the juice of the capsules under the name of [?] from an extract of the entire plant, [?], which he regarded as much less active. He described exactly how the capsules should be incised, the performing of which operation he designated by the verb [?]. We may infer from these statements of Dioscorides that the collection of opium was at that early period a branch of industry in Asia Minor. The same authority alludes to the adulteration of the drug with the milky juices of Glaucium and Lactuca, and with gum. Pliny devotes some space to an account of Opion, of which he describes the medicinal use. The drug is repeatedly mentioned as Lacrima papaveris by Celsus in the 1st century, and more or less particularly by numerous later Latin authors. During the classical period of the Roman Empire as well as in the early middle ages, the only sort of opium known was that of Asia Minor. The use of the drug was transmitted by the Arabs to the nations of the East, and in the first instance to the Persians. From the Greek word [?], juice, was formed the Arabic word Afyun, which has found its way into many Asiatic languages. The introduction of opium into India seems to have been connected with the spread of Islamism, and may have been favoured by the Mahommedan prohibition of wine. The earliest mention of it as a production of that country occurs in the travels of Barbosa who visited Calicut oh the Malabar coast in 1511. Among the more valuable drugs the prices of which he quotes, opium occupies a prominent place. It was either imported from Aden or Cambay, that from the latter place being the cheaper, yet worth three or four times as much as camphor or benzoin. Pyres in his letter about Indian drugs to Manuel, king of Portugal, written from Cochin in 1516, speaks of the opium of Egypt, that of Cambay and of the kingdom of Cous (Kus Bahar, S.W. of Bhotan) in Bengal. He adds that it is a great article of merchandize in these parts and fetches a good price;— that the kings and lords eat of it, and even the common people, though not so much because it costs dear. Garcia d’Orta informs us that the opium of Cambay in the middle of the 16th century was chiefly collected in Malwa, and that it is soft and yellowish. That from Aden and other places near the Erythrean Sea is black and hard. A superior kind was imported from Cairo, agreeing as Garcia supposed with the opium of the ancient Thebaid, a district of Upper Egypt near the modern Karnak and Luksor. In India the Mogul Government uniformly sold the opium monopoly, and the East India Company followed their example, reserving to itself the sole right of cultivating the poppy and selling the opium. Opium thebaicun was mentioned by Simon Januensis, physician to Pope Nicolas IV. (A.D. 1288-92), who also |

alludes to meconium as the dried juice of the pounded capsules and leaves. Prosper Alpinus, who visited Egypt in 1580-83, states that opium or meconium was in his time prepared in the Thebaid from the expressed juice of poppy heads. The German traveller Kampfer, who visited Persia in 1685, describes the various kinds of opium prepared in that country. The best sorts were flavoured with nutmeg, cardamom, cinnamon and mace, or simply with saffron and ambergris. Such compositions were called Theriaka, and were held in great estimation during the middle ages, and probably supplied to a large extent the place of pure opium. It was not uncommon for the sultans of Egypt of the 15th century to send presents of Theriaka to the doges of Venice and the sovereigns of Cyprus. In Europe opium seems in later times not to have been reckoned among the more costly drugs; in the 16th century we find it quoted at the same price as benzoin, and much cheaper than camphor, rhubarb, or manna. With regard to China it is supposed that opium was first brought thither by the Arabians, who are known to have traded with the southern ports of the empire as early as the 9th century. More recently, at least until the 18th century, the Chinese imported the drug in their junks as a return cargo from India. At this period it was used almost exclusively as a remedy for dysentery, and the whole quantity imported was very small. It was not until 1767 that the importation reached 1,000 chests, at which rate it continued for some years, most of the trade being in the hands of the Portuguese. The East India Company made a small adventure in 1773 ; and seven years later an opium depot of two small vessels was established by the English in Lark’s Bay, south of Macao. The Chinese authorities began to complain of these two ships in 1793, but the traffic still increased, and without serious interruption until 1820, when an edict was issued forbidding any vessel having opium on board to enter the Canton river. This led to a system of contraband trade with the connivance of the Chinese officials, which towards the expiration of the East India Company’s charter in 1834 had assumed a regular character. The political difficulties between England and China that ensued shortly after this event, and the so-called Opium War, culminated in the Treaty of Nanking (1842), by which five ports of China were opened to foreign trade, and opium was in 1858 admitted as a legal article of commerce. The vice of opium-smoking began to prevail in China in the second half of the 17th century, and in another hundred years had spread like a plague over the gigantic empire. The first edict against the practice was issued in 1796, since which there have been innumerable enactments and memorials,’ but all powerless to arrest the evil which is still increasing in an alarming ratio. Mr. Hughes, Commissioner of Customs at Amoy, thus wrote on this subject in his official Trade Report for the year 1870:— “Opium-smoking appears here as else where in China to be becoming yearly a more recognized habit,— almost a necessity of the people. Those who use the drug now do so openly, and native public opinion attaches no odium to its use, so long as it is not carried to excess. … In the city of Amoy, and in adjacent cities and towns, the proportion of opium-smokers is estimated to be from 15 to 20 per cent, of the adult population. … In the country the proportion is stated to be from 5 to 10 per cent. . . .’ (Pharmacographia, Fluckiger & Hanbury, 1879) |