Introduction to the Art of Distillation

Introduction

Distillation was a major turning point in Pharmacy, and therefore, also in Medicine. Through Distillation, the Essence of a liquid or plant could be separated from the more dense or earthy aspect. This produced a medicine which is clear and won’t corrupt like a decoction would, for example. The distillation of Wine gave Spirit (alcohol) which could be used to extract the virtues of plants. Likewise, aromatics could be distilled to give essential oils, useful in both Medicine and Perfumery.

As distillation began to be applied to metals and minerals, mineral acids such as Hydrochloric (from Salt), Nitric (from Saltpeter) and Sulphuric (from Vitriol) were produced. These then could be used to dissolve metals and minerals which were then prepared into various preparations such as Essence, Tinctures, Oils etc.

What is Distillation?

Distillation is basically the art of collecting steam, or separating Volatile from the Non-Volatile. When we boil a kettle of water, the steam that comes out is distilled water. If you place a cup over the spout where the steam comes out, the condensation that drops out of the cup is distilled water, and the process, distillation.

There are 2 main parts to distillation: heating the matter to be distilled, and condensing and collecting the steam which rises into a receiver.

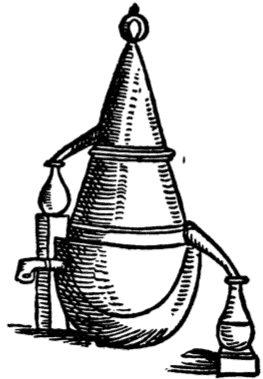

The three main parts of a Still are the Vessel containing the matter to be distilled, the Head (Alembic) where condensation takes place, and the Receiver, in which the distilled liquid is collected.

|

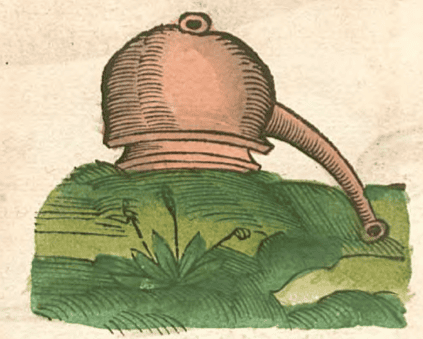

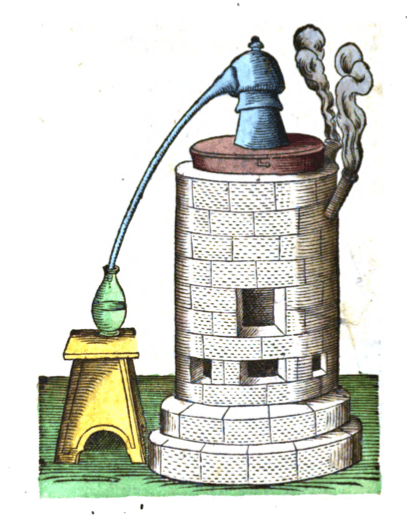

The Alembic is the earliest form of distillation apparatus. Heat is applied to the large vessel, the steam collects and condenses in the round head at the top (Alembic) and drops down into the smaller vessel (the Receiver) |

Basic Vessels of Distillation

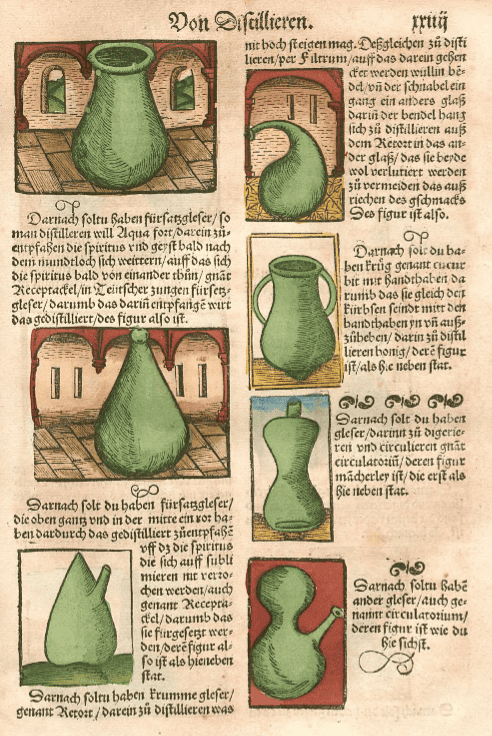

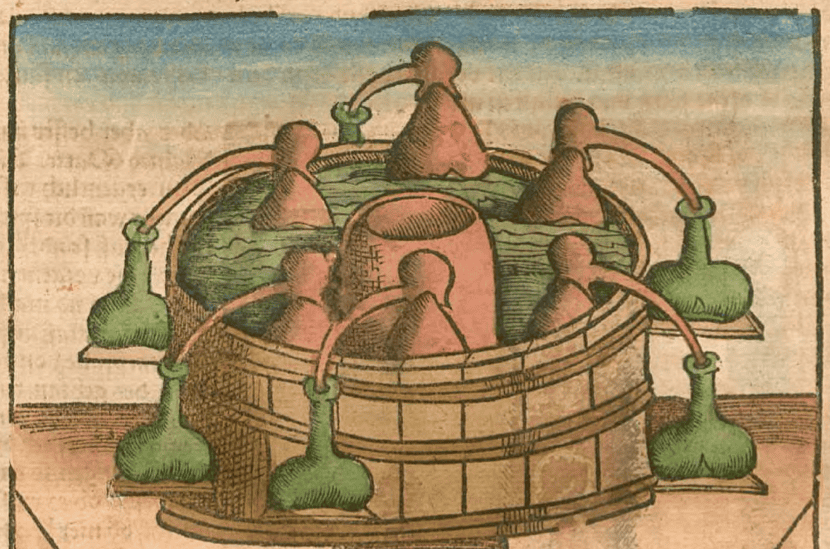

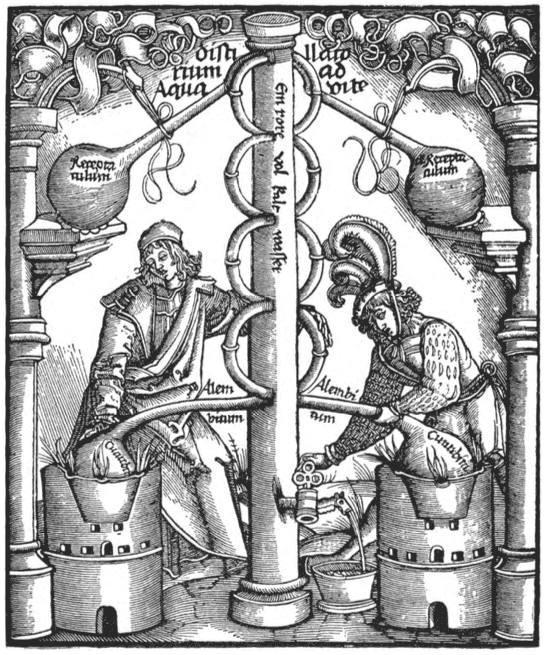

A page from showing different vessels from The Book of Distillation

A page from showing different vessels from The Book of Distillation (Das Buch von Distillieren), Brunschwig, 1532

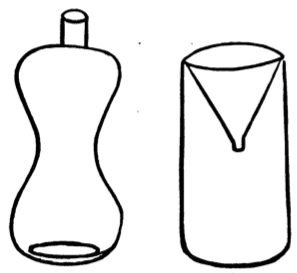

A Vial |

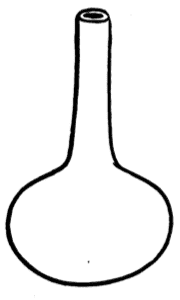

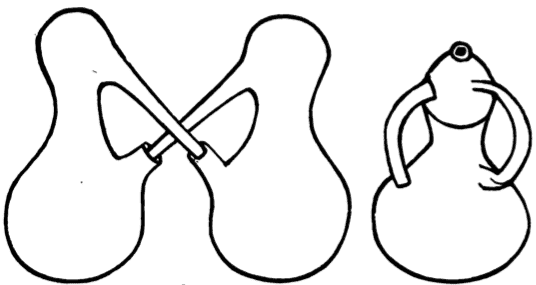

A Cucurbit, named from its similarity to a Gourd |

|

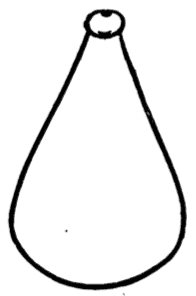

Left: Retort, a vessel with a long neck, used in distillation. Retorts were usually used as Receivers. Here we see 2 Retorts joined together, used in distilling very volatile substances. |

|

|

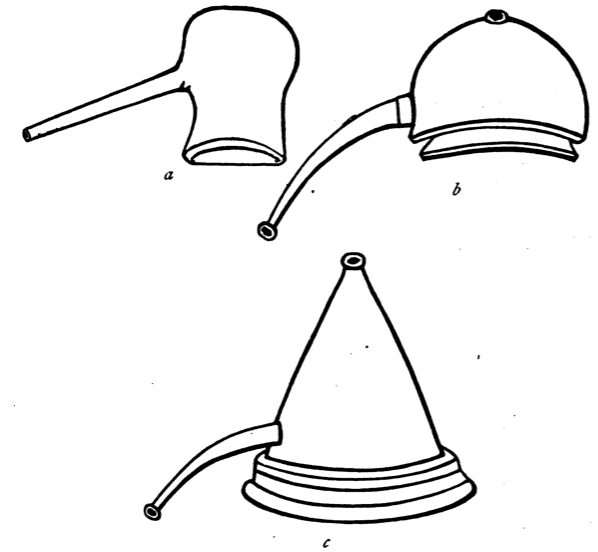

Alembics, or the ‘Head’ of the Still. These were early condensers and

were usually made of earthenware, copper or lead to facilitate cooling.

They were designed to increase surface area and thereby enhance

more efficient cooling.

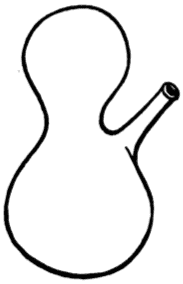

Left: Circulatories, they allow the distilled matter to circulate, or fall down to be distilled again, thereby collecting a more subtle distillate. |

Circulatory with a lateral ‘Beak’ |

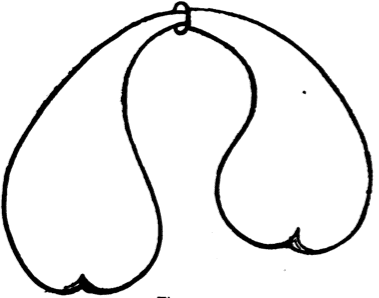

More elaborate Circulatories:

A Double Circulatory (left)

A ‘Pelican‘ (right) with 2 tubes for

returning fluid.

|

|

|

Refinements in Distillation

As the popularity of distillation increased, so it became more refined. Larger, more elaborate apparatus were conceived, and variations were developed suited for different purposes.

One of the early refinements was the use of a

water bath, or Balneo Marie, the Marian Bath.

The vessel containing matter to be distilled is

sat in a water bath and the water is heated.

This is especially useful for distilling herbs as

it prevents excess heat, the vessel only

reaching a maximum of boiling water

temperature (100 degrees C.).

A plate used to sit over a Water-Bath,

the round holes being for vessel to sit in.

This helped stop the boiling away of the Water.

|

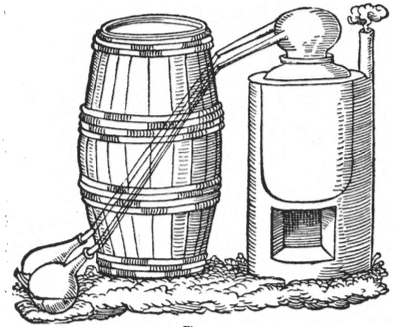

Another modification was in the condensing of the steam. Due to the heat of distillation, it was necessary to keep the head (Alembic) and collecting tube cool, to avoid loss in the form of steam, and this was achieved by running it through water. This example from Ryff (The Distillers Book, 1567) shows 2 pipes coming from the Head. It is better for small quantities and volatile substances. |

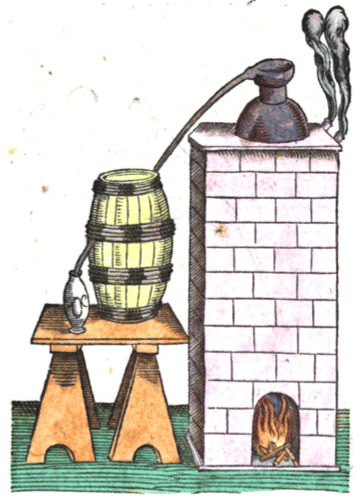

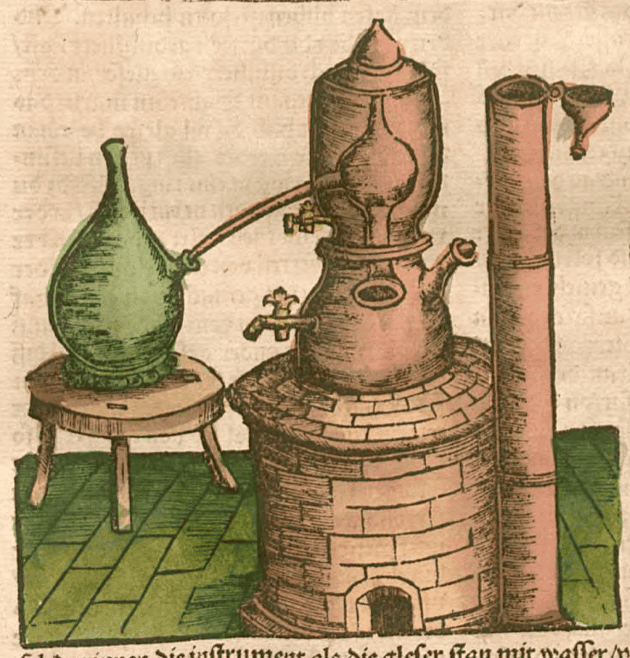

This version, also from Ryff, is suited

to distilling larger quantities.

A vessel such as this collects two fractions from one

distillation. The upper receiver will collect the more

pure or volatile, the lower, the denser or less refined.

For the apothecary, putting wine which has been

infused with a herb will give a spirit of the herb in the

upper receiver, and a distilled water of the herb in the

lower receiver.

Here we see a distilling apparatus as

may have been found in a 17th century Apothecary. The vessels began to be

made of Copper, and the Alembic is

seated inside a large copper vessel

of water (called a ‘Moor’s Head‘). This

greatly facilitated the condensing of

steam into water.

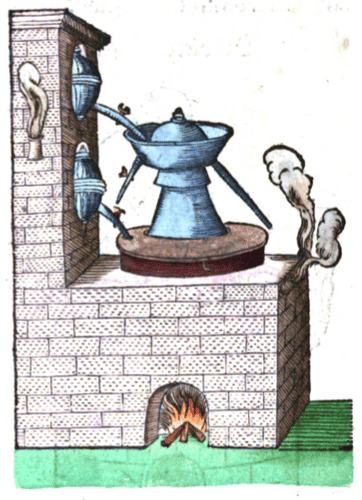

An improved Still. Only the most subtle

spirit will collect in the top Receivers,

the rest being returned to the bottom

vessel.

This type of apparatus is suitable for

rectifying alcohol to get high purity.

Stills similar to this are still used in the

distillation of spirits.

Often a sponge was put in the head

which would condense the water,

leaving the alcohol to pass through

to the receiver.

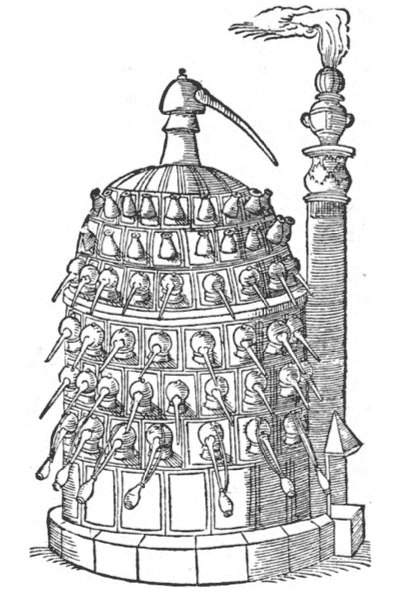

An apparatus used for multiple

distillations at one time.

The Herb Book of Matthiolus (1586) illustrated this

vessel which he said was in common use in Venice.

First, the fire is lit and allowed to make the entire

apparatus hot. Then, when the fire dies down, tiles

are used to block the flow of air in, thus maintaining

an even and lower temperature. Distillation is then

started. It is quick and efficient, capable of distilling

100 pounds of water in 24 hours.

Large commercial Copper Still at the José Cuervo Distillery in Tequila, Mexico

Large commercial Copper Still at the José Cuervo Distillery in Tequila, Mexico(Photo by Mdd4696) (Wikimedia)

Distillation for the Modern Practitioner

Small-scale Distillation for the modern practitioner can still be viable today. Distilled Waters of various herbs can be prepared with an infinite variety of floral waters being possible. Distilled spirits of herbs can be made which are similar to alcoholic tinctures, with a focus on the volatile aspects. Smaller glass distillation units can prepare things such as Oil of Spirit of Amber, for example.

As the knowledge of distillation increases, there are various mineral and metallic preparations which can also be prepared by distillation.

Home distillation equipment has become readily available and very affordable. Glass distillation kits are also cheap and available, meaning that to begin to delve into this fascinating aspect of Traditional Medicine is easily within reach for modern practitioners.

Some Traditional Distillation texts

–The vertuose boke of Distyllacyon of the waters of all maner of Herbes … Laurens Andrewe. London, 1527 (Downloadable)

–The Art of Distillation, John French, 1667

–The Art of Chymistry: as it is Now Practised, Pierra Thibaut, 1668

–A course of chymistry, Lemery, 1677

–The Works of Geber, 1686