Cinnamonum, Cinnamon, Cassia Lignea, Rou Gui 肉皮Cinnamon:–Gui Pi 桂皮 (TCM) –Tvak (Ayurveda) –Ilavankap Padtai (Siddha) –Dar Chini (Unani) –Shing tsha ཤིང་ཚ (Tibetan) Cassia Lignea: –Rou Gui 肉皮 (TCM) –Taj Qalmi (Unani) |

|

|

|

|

Cassia Lignea Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491 |

Cinnamon Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491 |

|

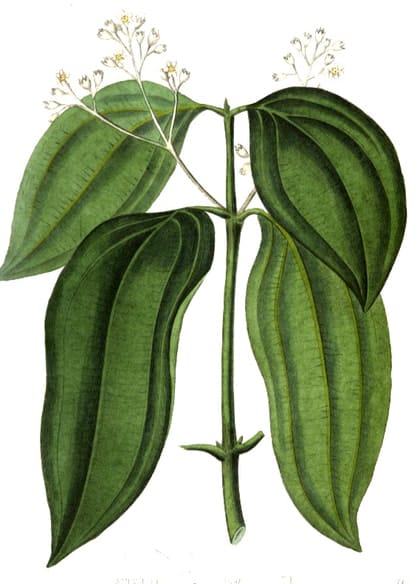

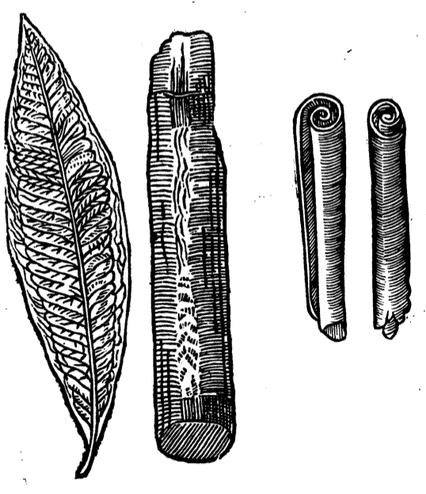

Above: Cinnamon leaf and bark (left); Cassia bark (right)

Above: Cinnamon leaf and bark (left); Cassia bark (right)Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum, 1640 Left: Cinnamon, Medical Botany, Stephenson and Churchill, 1836 |

|

|

|

Cinnamon Koehler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887 |

Cassia Koehler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887 |

Bulk Cinnamon at Chengdu Medicine Market (Adam, 2016)

Bulk Cinnamon at Chengdu Medicine Market (Adam, 2016) Packaging of imported Cinnamon bark. The dried bark is bundled

Packaging of imported Cinnamon bark. The dried bark is bundled into pacakages of half to 2 kg, then packed into bamboo boxes.

(A Manual of Organic Materia Medica and Pharmacognosy, Sayre, 1907)

Chinese Cinnamon bark (Adam, 2016)

Chinese Cinnamon bark (Adam, 2016)Botanical name:

There are several main Cinnamonum species:

- Ceylon or “True” Cinnamon–Cinnamonum zeylanicum (syn. C. verum)

- Cassia Lingea, Chinese Cinnamon, Chinese Cassia, Rou Gui–C. cassia

- Indonesian Cinnamon–Cinnamomum burmannii

- Vietnamese or Saigon Cinnamon–Cinnamomum loureiroi (regarded as best)

Parts used:

Bark

In TCM, if the peel is removed from the inside and outside of the bark, it is called Gui Xin, “Heart of Cassia”

See also Cinnamon leaf (Indian leaf) and Cinnamon twig

Temperature & Taste:

Hot, dry. Pungent

“Hot and Dry in the Third degree”. (Avicenna)

Classifications:

2A APERIENT. 2B ATTENUATER. 2F. PURIFYING. 2H. CARMINATIVE. 2P. HEMOSTATIC

3C. ALEXIPHARMIC. 3D. CORDIALS & CARDIACS. 3G. EMMENAGOGUE. 3L. ANTI-TUSSIVE

4a. CEPHALIC. 4c. CARDIAC. 4e. STOMACHIC. 4f. SPLENETIC. 4g. HEPATIC. 4h. NEPHRITIC. 4i. UTERINE. 4j. NERVINE

TCM:

M. Warm to Expel Cold

Uses:

1. Warms the Stomach, Clears Cold:

-good in all cold diseases of the Head, Stomach and Womb

-benefits Digestion, helps Digestion, increases Appetite, abdominal pain or distention, abdominal masses

-chronic Diarrhea

-special function of helping distribute nutrition (West)

-“tonifies a condition of general debility”. (TCM: Ming Yi Bie Lu)

-“To stop lower abdominal pain in autumn and winter, Rougui is the only choice”. (TCM: Zhang Yuan Su)

-“Its dissolving properties facilitate the Purgative Drugs to elicit their affects”. (Avicenna)

2. Warms the Kidneys, Benefits Yang:

-Edema, Fluid Retention, Cold-type Back Pain

-Leukorrhea, Spermatorrhea

-Chronic Diabetes

-Impotence, Frigidity

-Cold extremities

–useful in Cold Kidney and Bladder pain. (Avicenna)

-“Dissolves Hard and Cold Visceral Swellings”. (Avicenna)

-Cold-Damp joint pain, Arthritis; “good for treating arthralgia due to invading pathogenic Cold”. (Li Shi Zhen)

-lowers the Yang back to its source in the lower abdomen (Dan Tian) (TCM)

-Regarded as Tonic to the 7 Body Tissues (Rasayana)

-“Long-term use prevents aging and enables one to enjoy a long life”. (TCM: Ming Yi Bie Lu)

3. Warms the Uterus, Promotes Menstruation and Birth:

-promotes Menstruation when obstructed by Cold

-Promotes Birth (1 dram taken with wine)

-expels Afterbirth

-very useful for Menopause

-“Some physicians opine that the Cassia bark helps to expel the Fetus”. (Avicenna)

4. Warms the Uterus, Stops Bleeding:

-Uterine Bleeding, excessive Menstruation associated with Cold

-Postpartum Hemorrhage

-diseases of Pregnancy: Edema, Hypertension, Lumbago, Bleeding during pregnancy, Threatened Miscarriage

-other types of passive bleeding: Hemoptysis etc.

5. Warms the Heart, Cheers the Spirit, benefits Circulation:

-Cold chest pain, poor circulation

-Dizziness, Vertigo, Hypertension

-refreshes Spirits, good in weakness

-regarded as Exhilarant (Avicenna)

-also for Dim and Dark vision (Avicenna)

6. Clears Wind-Cold, Resists Poison:

-Influenza, Plague, Cholera

-used for Fevers

-“Cassia bark is taken orally in case of Snake Poisoning”. (Avicenna)

7. Warms the Lungs, stops Wheezing:

-Asthma, Bronchitis, difficulty Breathing, Consumption

-“It is useful in Chest affections”. (Avicenna)

8. Externally:

-oil is applied to Warts

-with Honey to remove Birthmarks and Freckles (Dioscorides)

-“Cassia bark is painted with honey on Acne”. (Avicenna)

-Headache, Rheumatic or Muscle pains are treated by applying a paste of the powder mixed with warm water

-applied to Insect and Scorpion bites (Avicenna)

Dose:

Decoction: 1 ½–5 grams

Powder: 250mg–2 grams

Comment:

Cinnamon twig (Gui Zhi) is regarded as thin and light whereas Cinnamon (or Cassia) bark is thick and heavier. Cinnamon twig therefore moves up and clears (Wind-Cold-Damp from) the Exterior, while Cinnamon (or Cassia) moves inwards and downwards, and warms and strengthens the Kidneys.

Correctives:

1. Tragacanth

2. Valerian

Substitutes:

1. Cassia can be substituted for Cinnamon and vice versa.

2. Indian leaf (Cinnamonum tamala leaf)

3. Double the amount of Cubeb or Juniper berry (Avicenna)

Main Combinations:

Cinnamon & Licorice

Cinnamon, Clove & Nutmeg

Cinnamon, Greater Cardamon, Cinnamon leaf (or Clove) (Trijata, the ‘Three Aromatics’ of Ayurveda)

Stomach, Digestion:

1. To warm the Stomach and Digestion:

i. Cinnamon with Ginger, Cardamon (as in Pulvis Aromaticus); this combination has also been used in Ayurveda.

ii. Cinnamon, Greater Cardamon, Indian leaf (Trijata, the ‘Three Aromatics’ of Ayurveda)

iii. Cinnamon with Citron peel, Mastic, Sugar of Rose (as in Powder to Strengthen the Stomach)

iv. Cinnamon with Ginger, Clove, Galangal, Nutmeg

2. To strengthen the Stomach and Spleen:

i. Cinnamon with Elecampane and Cumin (as in Powder of Cinnamon Compound of Mesue)

ii. Cinnamon with Rose, Sandalwood, Licorice (as in Aromaticum Rosatum)

iii. Cassia Lignea, Fennel seed, Mastic (The Secrets of Alexis, 1615)

3. To increase Appetite:

i. Cinnamon with Ginger, Bitter Orange peel

ii. Cinnamon with Fennel seed, Parsley seed and Clove

4. Nausea, Vomiting:

i. Cinnamon powder taken with an infusion of fresh Ginger root

ii. Cinnamon Water with Syrup of Lemon (A Treatise on Foreign Drugs, Geoffroy and Thicknesse, 1749)

5. To increase strength:

i. Cinnamon with Balm, Blessed Thistle (A Treatise on Foreign Drugs, Geoffroy and Thicknesse, 1749)

ii. Cinnamon with Elecampane, Licorice

iii. Cinnamon with confected Chebulic Myrobalan, confected Ginger

iv. Cinnamon, Date, Almond, Mastic

v. Cinnamon with Astragalus Huang Qi and Atractylodes Bai Zhu

Urinary, Kidneys

6. To Warm the Kidneys:

i. and as an Aphrodisiac, Cinnamon with Cardamon, Long Pepper, Licorice, Dates, Raisins and Honey (as in Eladi Pills, Ayurveda)

ii. for Back pain, Leukorrhea, Kidney weakness, Cinnamon with Nutmeg, Elecampane, Tormentil, Clove (as in Powder of Nutmeg)

iii. Cinnamon with Walnut, Juniper

7. Edema

i. Kidney cold, Cinnamon with Parsley seed, Juniper berry

ii. from Cold, Cinnamon with Squill

iii. Cinnamon with Asarum, Mastic, Wormwood, Aniseed, Fennel, Rhubarb, Indian Spikenard (as in Antidote for Edema of Nicholas)

8. Infertility, Cinnamon with Ram Testicles, Hare Uterus, Mace, Clove, Ginger, Saffron, Walnut (as in Decoction for Sterility)

9. Arthritis, Cinnamon with Currant, Guaiacum, China root, Licorice, Calamus, Barley (as in Decoction for Arthritis)

Gynecology, Obstetrics

10. Promote Menstruation:

i. Cinnamon and Myrrh (Dioscorides)

ii. Cinnamon with Iron

iii. Cinnamon with Saffron, Iron

iv. Cinnamon with Bay berry, Rosemary, Juniper berry, Saffron (as in Decoction Against Retention of Menstruation)

11. Menstrual Pain, Dysmenorrhea:

i. from Cold, Cinnamon with Fennel seed, Pennyroyal

ii. from Cold, Cinnamon with Fennel seed, Ginger (this has been studied: see below)

iii. from Blood stagnation, Cinnamon with Saffron, Myrrh

iv. Uterine congestion, Cinnamon, Turmeric, Ginger, Saraca

12. Leukorrhea, with Agnus Castus, Rue, Fennel

13. To prepare for Birth, take Cinnamon with Licorice for 2 weeks before the due date. (Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives)

14. To promote Labor:

i. Cinnamon with Saffron and Amber (as in Birth Powder)

ii. Cinnamon with Pennyroyal, Mugwort, Cassia Fistula, Saffron, Myrrh (as in Powder to Facilitate Birth)

15. Postpartum Pain:

i. Cassia wood, Cinnamon with Maidenhair, Aniseed, Raisins (as in Powder Against Postpartum Pain)

ii. Cinnamon with Amber, Peach kernel, Comfrey root

Other:

16. Lung congestion from Cold Phlegm, with Long Pepper, Adhatoda vasica, Tabasheer (Ayurveda)

17. To preserve from Poison and Infection:

i. Cinnamon with Blessed Thistle

ii. Cinnamon with Saffron, Myrrh, Costus, Spikenard

18. To strengthen the Heart and Circulation:

i. Cinnamon with Licorice; used for sweating, rapid Heart beat and Palpitations. (TCM)

ii. Cinnamon with Saffron, Amber

iii. Cinnamon with Rose, Amber, Bugloss, Balm, Saffron, Red Coral, Sandalwood (as in Powder to Strengthen the Heart)

iv. Cinnamon with Arjuna, Turmeric, Guggulu (Ayurveda)

19. Hemorrhoids:

i. Cinnamon with Caraway (Avicenna)

ii. Cinnamon, Aniseed, Fennel seed, Bdellium

Major Formulas

Infusion Purging Bile

Powder of Cinnamon Compound (Diacinnamonum) (Mesue)

Powder to Strengthen the Stomach and Digestion

Powder to Strengthen the Stomach (Nicholas)

Decoction Against Retention of Menstruation

Decoction for Sterility (Quercetan)

Powder Against Postpartum Pain

Powder for Loss of Appetite Greater (Nicholas)

Powder for Edema (Nicholas)

Antidote for Edema (Nicholas)

Powder for Leukorrhea

Powder to Promote Menstruation (Riverius)

Birth Powder

Powder to Facilitate Birth (Renodeus)

Powder to Cleanse the Afterbirth

Electuary of Sulphur (Unani)

Tincture of Life (Mynsichts)

Bao Yuan Tang

Jiao Tai Wan

Mu Xiang Liu Qi Yin

Ren Shen Yang Rong Tang

Shi Quan Da Bu Tang

Shao Fu Zhu Yu Tang

You Gui Yin

You Gui Wan

Sitopaladi Powder (Ayurveda)

Nutmeg Powder (Jatiphaladi Churna) (Ayurveda)

Pomegranate 5 (Se bru 5) (Tibetan Medicine)

Tabasheer 9

Raisin 7 (Tibetan Medicine)

1. Compound Powder of Cinnamon:

i. Cinnamon (2 oz.), Cardamon seed (1 ½ oz.), Ginger (1 oz.), Long Pepper (half oz.). (London)

ii. Cinnamon, Lesser Cardamon (2 oz. each), Ginger, Clove (½ oz. each) (Pharmacopoeia regni Poloniae, 1817)

iii. Cinnamon (2 oz.), Cardamon, Ginger, Nutmeg (1 oz. each) (Formulaire Magistral et Memorial Pharmaceutique, 1823)

iv. Cinnamon, Cardamon, Ginger, Nutmeg (1 oz. each) (Pharmacopoeia Amstelodamensis, 1792)

v. Elecampane, Calamus, Ginger, Aniseed, Orange peel, Black Pepper (1 oz. each), Clove, Cinnamon (½ oz. each). (Armen Pharmacopoea, Hufeland, 1825)

2. Compound Tincture of Cinnamon:

i. Cinnamon (6 drams), Cardamon seed (3 drams), Ginger, Long Pepper (2 drams each), Proof Spirit (2 pints). (London)

ii. Cinnamon, Lesser Cardamon (1 oz. each), Long Pepper (2 drams), Proof Spirit (2 ½ pounds). (Edinborough)

iii. Cinnamon (2 oz.), Lesser Cardamon, Clove, Galangal, Ginger (half oz. each), Alcohol (2 lbs.). (Pharmacopoeia Oldenburgica, 1801)

iv. Cinnamon, Calamus, Lesser Galangal (1 oz. each), Peppermint, Fresh Lemon peel (1 ½ oz. each), Lesser Cardamon, Ginger (2 drams each), Alcohol (30 oz.). Digest 4 days, express, filter. (Dispensarium Lippiacum, 1792)

3. Aromatic Stomach Tincture:

i. Cinnamon (1 oz.), Clove, Nutmeg, Saffron (half oz. each), Calamus (6 drams), Mace (2 drams), fresh Lemon peels (2), fresh Orange peel (1), Alcohol (1 ½ pound). Digest, express, filter. Dose: 50–80 drops. (Pharmacopoeia Wirtembergica, 1798)

Cautions:

1. Not used during pregnancy in Heat conditions

2. Not used in people with excess Heat.

3. Not used in Heat-type Bleeding

4. “It is a drug that should not be used in spring and summer” (TCM: Zhang Yuan Su)

Safety

–Safety of Cinnamon: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Randomized Clinical Trials

Main Preparations used:

Confection, Distilled Water, Tincture of Cinnamon, Distilled Oil, Salt from the Ashes, Syrup of Cinnamon, Magistery of Cinnamon;

Tincture of Cinnamon:

i. Cinnamon (3 oz.), Proof Spirit (2 pints). Macerate 14 days, strain. (London)

- More Info

- History

- Research

|

‘Cinnamon was held in high esteem in the most remote times of history. In the words of the learned Dr. Vincent Dean of West minster, it seems to have been the first spice sought after in all oriental voyages. Both cinnamon and cassia are mentioned as precious odoriferous substances in the Mosaic writings and in the Biblical books of Psalms, Proverbs, Canticles, Ezekiel and Revelations, also by Theophrastus, Herodotus, Galen, Dioscorides, Pliny, Strabo and many other writers of antiquity: and from the accounts which have thus come down to us, there appears reason for believing that the spices referred to were nearly the same as those of the present day. That cinnamon and cassia were extremely analogous, is proved by the remark of Galen, that the finest cassia differs so little from the lowest quality of cinnamon, that the first may be substituted for the second, provided a double weight of it be used. It is also evident that both were regarded as among1 the most costly of aromatics, for the offering made by Seluucus II. Callinieus, king of Syria, and his brother Antiochus Hierax, to the temple of Apollo at Miletus, B.C. 243, consisting chiefly of vessels of gold and silver, and olibanum, myrrh, costus, included also two pounds of Cassia, and the same quantity of Cinnamon. In connexion with this subject there is one remarkable fact to be noticed, which is that none of the cinnamon of the ancients was obtained from Ceylon. “In the pages of no author,” says Tennent, “European or Asiatic, from the earliest ages to the close of the thirteenth century, is there the remotest allusion to cinnamon as an indigenous production, or even as an article of commerce in Ceylon.” Nor do the annuals of the Chinese, between whom and the inhabitants of Ceylon, from the 4th to the 8th centuries, there was frequent intercourse and exchange of commodities, name Cinnamon as one of the productions of the Island. The Sacred Books and other ancient records of the Singhalese are also completely silent on this point. Cassia, under the name of Kiwi, is mentioned in the earliest Chinese herbal,— that of the emperor Shen-nung, who reigned about 2700 B.C., in the ancient Chinese Classics, and in the Rh-ya, a herbal dating from 1200 B.C. In the Hai-yau-pen-ts’ao, written in the 8th century, mention is made of Tien-chu kwei. Tien-chu is the ancient name for India: perhaps the allusion may be to the cassia bark of Malabar. In connexion with these extremely early references to the spice, it may be stated that a bark supposed to be cassia is mentioned as imported into Egypt together with gold, ivory, frankincense, precious woods, and apes, in the 17th century B.C. The accounts given by Dioscorides, Ptolemy and the author of the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, indicate that cinnamon and cassia were obtained from Arabia and Eastern Africa; and we further know that the importers were Phoenicians, who traded by Egypt and the Red Sea with Arabia. Whether the spice under notice was really a production of Arabia or Africa, or whether it was imported thither from Southern China (the present source of the best sort of cassia), is a question which has excited no small amount of discussion. We are in favour of the second alternative,— firstly, because no substance of the nature of cinnamon is known to be produced in Arabia or Africa; and secondly, because the commercial intercourse which was undoubtedly carried on by China with India and Arabia, and which also existed between Arabia, India and Africa, is amply sufficient to explain the importation of Chinese produce. That the spice was a production of the far East is moreover implied by the name Darchini (from dar, wood or bark, and Chini, Chinese) given to it by the Arabians and Persians. If this view of the case is admissible, we must regard the ancient cinnamon to have been the substance now known as Chinese Cassia Lignea or Chinese Cinnamon, and cassia as one of the thicker and perhaps less aromatic barks of the same group, such in fact as are still found in commerce. Of the circumstances which led to the collection of cinnamon in Ceylon, and of the period at which it was commenced, nothing is known. That the Chinese were concerned in the discovery is not an unreasonable supposition, seeing that they traded to Ceylon, and were in all probability acquainted with the cassia-yielding species of Cinnamomum of Southern China, a tree extremely like the cinnamon tree of Ceylon. Whatever may be the facts, the early notices of cinnamon as a production of Ceylon are not prior to the 13th century. The very first, according to Yule, is a mention of the spice by Kazwini, an Arab writer of about A.D. 1275, very soon after which period it is noticed by the historian of the Egyptian Sultan Kelaoun, A.D. 1283. The prince of Ceylon is stated to have sent an ambassador, Al-Hadj-Abu-Othman, to the Sultan’s court. It was mentioned that Ceylon produced elephants, Bakam (the wood of Cassalpinia Sapan L., pearls and also cinnamon. A still more positive evidence is due to the Minorite friar, John of Montecorvino, a missionary who visited India. This man, in a letter under date December 20th, 1292 or 1293, written at Mabar, citta dell India di sopra,” |

and still extant in the Mediccan library at Florence, says that the cinnamon tree is of medium bulk, and in trunk, bark and foliage, like a laurel, and that great store of its bark is carried forth from the island which is near by Malabar. Again, it is mentioned by the Mahomedan traveller Ibn Batuta about A.D. 1340, and a century later by the Venetian merchant Nicolo di Conti, whose description of the tree is very correct. The circumnavigation of the Cape of Good Hope led to the real discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1505, and to their permanent occupation of the island in 1530, chiefly for the sake of the cinnamon. It is from the first of these dates that more exact accounts of the spice began to reach Europe. Thus in 1511 Barbosa distinguished the fine cinnamon of Ceylon from the inferior Canella trista of Malabar. Garcia de Orta, about the middle of the same century, stated that Ceylon cinnamon was forty times as dear as that of Malabar. Clusius, the translator of Garcia, saw branches of the cinnamon-tree as early as 1571 at Bristol and in Holland. At this period cinnamon was cut from trees growing wild in the forests in the interior of Ceylon, the bark being exacted as tribute from the Singhalese kings by the Portuguese. A peculiar caste called chalias, who are said to have emigrated from India to Ceylon in the 13th century, and who in after-times became cinnamon-peelers, delivered the bark to the Portuguese. The cruel oppression of these chalias was not mitigated by the Dutch, who from the year 1656 were virtually masters of the whole seaboard, and conceded the cinnamon trade to their East India Company as a profitable monopoly, which the Company exercised with the greatest severity. The bark previous to shipment was minutely examined by special officers, to guard against frauds on the part of the chalias. About 1770 De Koke conceived the happy idea, in opposition to the universal prejudice in favour of wild-growing cinnamon, of attempting the cultivation of the tree. This project was carried out under Governors Falck and Vander Graff with extraordinary success, so that the Dutch were able, independently of the kingdom of Kandy, to furnish about 400,000 Ib. of cinnamon annually, thereby supplying the entire European demand. In fact, they completely ruled the trade, and would even burn the cinnamon in Holland, lest its unusual abundance should reduce the price. After Ceylon had been wrested from the Dutch by the English in 1796, the cinnamon trade became the monopoly of the English East India Company, who then obtained more cinnamon from the forests, especially after the year 1815, when the kingdom of Kandy fell under British rule. But though the chalias had much increased in numbers, the yearly production of cinnamon does not appear to have exceeded 500,000Ib. The condition of the unfortunate chalias was not ameliorated until 1833, when the monopoly granted to the Company was finally abolished, and Government, ceasing to be the sole exporters of cinnamon, permitted the merchants of Colombo and Galle to share in the trade. Cinnamon however was still burdened with an export duty equal to a third or a half of its value; in consequence of which and of the competition with cinnamon raised in Java, and with cassia from China and other places, the cultivation in Ceylon began to suffer. This duty was not removed until 1853. The earliest notice of cinnamon in connection with Northern Europe that we have met with, is the diploma granted by Chilperic II., king of the Franks, to the monastery of Corbie in Normandy, A.D. 716, in which provision is made for a certain supply of spices and grocery, including 5 Ib. of Cinnamon. The extraordinary value set on cinnamon at this period is remarkably illustrated by some letters written from Italy, in which mention is here and there incidentally made of presents of spices and incense. Thus in A.D. 745, Gemmulus, a Roman deacon, sends to Boniface, archbishop of Mayence (“cum magna reverentia“), 4 ounces of Cinnamon, 4 ounces of Costus, and 2 pounds of Pepper. In A.D. 748, Theophilacias, a Roman archdeacon, presents to the same bishop similar spices and incense. Lullus, the successor of Boniface, sends to Eadburga, abbatissa Thanetensis, circa A.D. 732-751— “unum graphium argenteum, et utoracis et cinnamomi partem aliquam” ; and about the same date, another present of cinnamon to archbishop Boniface is recorded. Under date A.D. 732-742, a letter is extant of three persons to the abbess Cuneburga, to whom the writers offer— “turis et piperis et cinnamomi periodica xenia, sed omni mentis affectione destinata.” In the 9th century, Cinnamon, pepper, costus, cloves, and several indigenous aromatic plants were used in the monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland as ingredients for seasoning fish. Of the pecuniary value of this spice in England, there are many notices from the year 1204 downwards. In the 16th century it was probably not plentiful, if we may judge from the fact that it figures among the New Year’s gifts to Philip and Mary (1556-57), and to Queen Elizabeth (1561-62). (Pharmacographia, Fluckiger & Hanbury, 1879) |