Cannabis Flos, Cannabis flower

Marijuana, Marihuana, HempDa Ma, Ma Hua (TCM)

Qinnab (Unani)

Vijaya (Ayurveda)

Kanca (Siddha)

So ma nag po སོ་མ་ནག་པོ་ (Tibetan Medicine)

Herbarius latinus, Petri, 1485

Herbarius latinus, Petri, 1485 |

Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491

Ortus Sanitatis, Meydenbach, 1491 |

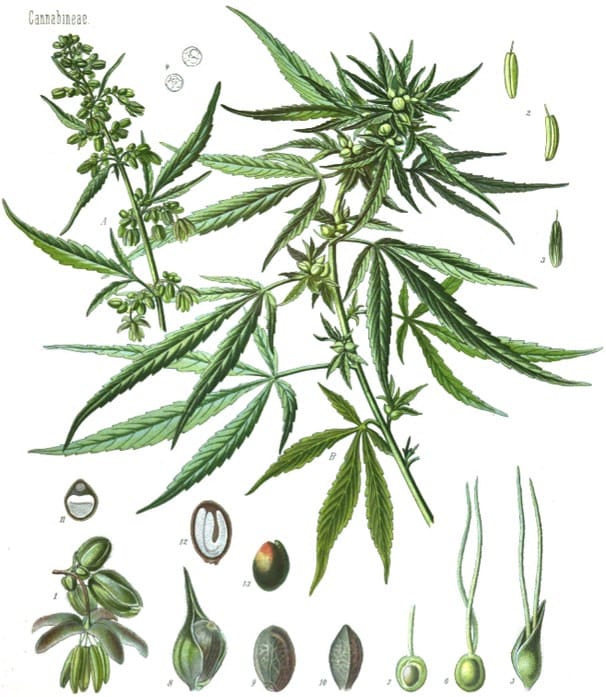

Kohler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887

Kohler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887

|

|

|

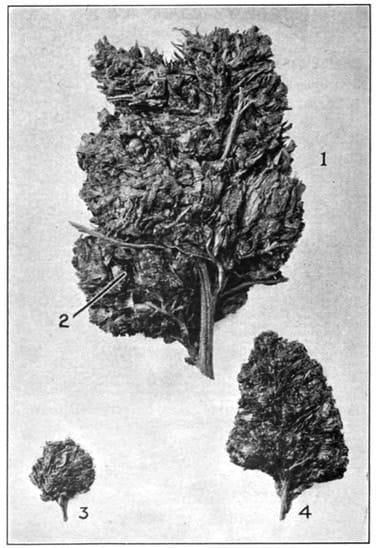

AFRICAN CANNABIS, PRESSED INTO DISCS 1, Portion of a disk composed of the compressed drug. 2, Single stem with flowers, fruits and bracts. 3. Irregular fragment of the drug. |

INDIAN CANNABIS 1. Large resinous branch. 2, Seed. 3, Small branches without seed. 4. Larger branch. |

Botanical name:

Cannabis sativa, C. indica

Parts used:

Flowering tops; Resin (Hashish)

See also Cannabis Seed

Temperature & Taste:

Warm, dry (some said Cold); Pungent

‘bitter, slightly hot and nontoxic’ (Zhen Quan)

Classifications:

2I. ANTISPASMODIC. 2R. NARCOTICS & HYPNOTICS

3I. APHRODISIAC

It has the following actions according to Unani texts:

1. Aphrodisiac; 2. Sedative; 3. Retentive; 4. Intoxicating; 5. Exhilarating; 6. Contracting; 7. Stomachic; 8. Anti-convulsive; 9. Analgesic; 10. Resolves Swellings

Uses:

1. Calms the Mind and Spirit:

-Hysteria, Depression, Melancholy, Nervousness, Insomnia, Nightmares

-traditionally for Mania and Insanity (Unani, India)

-‘It is a remedy for disordered mental action… in the wakefulness of old age, the restlessness of nervous exhaustion, and in Melancholia, it is an important remedy’. (Ellingwood)

-‘good for treating Amnesia’ (Li Shi Zhen)

2. Moves the Qi, Stops Wind, Eases Pain:

-Neuralgia, Migraine, Cancer pain

-Tetanus, Epilepsy, Vertigo, Tinnitus, Convulsions, Tremors

-Spasmodic Cough including Whooping Cough; Asthma

-effective for Glaucoma

3. Moves the Blood, Relieves Pain:

-Hysteria, Menorrhagia, Metrorrhagia, Dysmenorrhea, Menopausal symptoms

-pain of the gastrointestinal tract

-Tumors; recently found effective against various Cancers

4. Clears Heat and Damp, Promotes Urine:

-Difficult, Burning and Painful urine, chronic Cystitis

-Gonorrhea

5. Promotes Appetite, Benefits Stomach:

-stimulates appetite, especially when hindered by stress and worry

-nausea and poor appetite associated with Chemotherapy or radiotherapy

-Diarrhea and bowel complaints (Unani)

6. Clears Wind, Resists Poison:

-‘disperses invading pathogenic Wind of 120 kinds’ (Yao Xing Ben Cao)

-early stages of Cerebro-Spinal Meningitis

-antidote to Opium and Aconite poisoning.

-inhaled smoke was used for Orpiment poisoning in India

7. Aphrodisiac;

-used as an aphrodisiac in various traditions (as Confection or Electuary)

-prevents Premature Ejaculation

9. Externally:

-good for burns

-juice is dropped into the ears for deafness

-a paste with milk is applied to Hemorrhoids (Unani)

-applied to the forehead for Insomnia, Delirium and Insanity

Dose:

Powder of the Flower: 100–250mg

Tincture (1:10 in 45% alcohol): 5–15 drops (up to 60 drops)

Fluid Extract: 1–3, or 5 drops (up to 15 drops)

Solid Extract (B.P)/Resinous Extract (‘Hashish’): 30–120mg

Correctives:

1. Butter; Ghee

2. Calamus is regarded as corrective to the narcotic effects, and prevents mental deterioration; it has been smoked with Cannabis or can be taken orally.

3. Black Pepper

4. “Oxymel removes the harmful effects” (Avicenna)

Comment:

The medical genius – a guide to the cure (Jones, 1887) made an interesting distinction between the Therapeutic effects of Cannabis indica versus C. sativa:

GENERAL INDICATIONS for Cannabis Indica:

Mind lost in revery—lofty and sublime thoughts—magnified ideas of things of space and time—mental deception in regard to the flight of time, constant imagination of being too late—the brain feels expanded—craving for drink with dread of water—ravenous hunger.

GENERAL INDICATIONS for Cannabis Sativa:

Flow of urine, painful, burning—sense of heat about the heart—feeling as of water dropping down from the heart, or from other parts—ailments worse from talking.

Substitutes:

1. Poppy; Lettuce seed; Henbane (Unani)

2. Ergot (Waring)

Main Combinations:

1. Visceral pain: combine Cannabis with Lupulin (Hops resin) and Valerian (as in Compound Tincture of Cannabis, 1910)

2. Aphrodisiac:

i. Cannabis with Nutmeg and Pyrethrum (Unani)

ii. Aphrodisiac and to retain semen (prevent premature ejaculation), Cannabis with Orchis, Galangal, Almond, Nutmeg, Cinnamon, Saffron (Unani)

3. Obstructed and painful Menstruation, decoct Cannabis flowers with Feverfew and Pennyroyal

4. Flooding or Excessive Menstruation: 5 drops of the Tincture (10%) every half hour is “Specific”.

4. Hysteria, Cannabis with Asafetida (Unani)

5. Migraine:

i. Extract of Cannabis (12 grains), Camphor (20 grains), Extract of Henbane (24 grains). Make 12 pills. Take one at night. Repeat every 2 hours to produce sleep if necessary. (Vitalogy, 1906)

ii. Cannabis with Belladonna

6. As an anesthetic, Cannabis flower, Datura flower (equal parts). Powder, take 3 qian (9 grams) with wine. Shortly after, the person will ‘get drunk and tend to sleep’. (Li Shi Zhen)

7. Chronic Rheumatism, Extract of Cannabis (15 grains), Extract of Datura (10 grains), Aloe powder (10 grains), Extract of Colchicum (22 grains), Iron Sulphate (45 grains). Mix. Make 45 pills. Take one before each meal. (Vitalogy, 1906)

8. Acute Dysentery, infantile Convulsions, intestinal, hepatic and renal Colic, Cannabis with Sugar and Black Pepper (Unani)

9. Amenisa, and to ‘become knowldgeable of all manner of things’: Taoists combined Cannabis flower with Ginseng. Powder and steam them, and take some each night before bed, (Ben Cao Gang Mu)

Major Formulas

Nutmeg Powder (Jatiphaladi Churna) (Ayurveda)

Sarpagandha Ghana Vati (Ayurveda)

1. COMPOUND TINCTURE of CANNABIS. (1910)

Lupulin (Hops resin) 3 parts

Valerian Root 3 parts

Cannabis 2 parts

Tincture 1:4 in 65% alcohol. When finished, add enough fresh Pulsatilla Tincture to bring final strength to a 1:5 potency.

Used as a narcotic-analgesic, especially for referred visceral pain.

Dose 15-45 drops as needed.

Cautions:

One of the safest herbs in existence, as far as Safety Factor and LD50 is concerned. It is unique as a medicinal herb in being so potent in small dose, and yet has no known lethal dose in humans, even in massive dose, and has few side effects relative to its potency. It has been called the safest therapeutically active substance known to man.

1. People with predisposition to psychosis, psychotic episodes, schizophrenia and similar mental disturbance may experience aggravation or initiation, but there is no strong evidence showing a causative effect. It has been associated with Psychotic episodes in susceptible people but does not increase the percentage of schizophrenia and psychosis in epidemilogical studies comparing cultures with widespread use compared to cultures with little use.

2. According to Unani and Ayurvedic sources chronic heavy use may cause indigestion, general debility, poor appetite, cough, melancholy, impotency and dropsy. The Holy Men of India who use it habitually say it ‘destroys the Blood’ with heavy usage.

Main Preparations used:

Resin (Hashish), Oil, Extract, Tincture

1. EXTRACT of CANNABIS.

Exhaust Indian Hemp, in coarse powder, with alcohol (90%) by percolation; then evaporate to a soft extract.

Dose: ¼-1 grain (0.015-0.06 gram)

2. TINCTURE of CANNABIS.

Dissolve 1 part of the above Extract in alcohol (90%), enough to yield 20 parts. (1 in 20)

Alternatively, a 1 in 20 Tincture can be prepared by steeping 5 grams of Cannabis in 100mls of Brandy or Vodka.

Dose: 5-15 minims (0.3-1 ml)

-

Extra Info

-

Cannabis Products

-

History

- Research

|

1. Bhang, Siddhi or Subzl (Hindustani); Hashish or Qinnaq (Arabic). This consists of the dried leaves and small stalks, which are of a dark green colour, coarsely broken, and mixed with here and there a few fruits. It has a peculiar but not unpleasant odour, and scarcely any taste. In India, it is smoked either with or without tobacco, but more commonly it is made up with flour and various additions into a sweetmeat or majun, of a green colour. Another form of taking it is that of an infusion, made by immersing the pounded leaves in cold water. 2. Ganja (Hindustani); Qinnab (Arabic); Guaza of the London drug-brokers. These are the flowering or fruiting shoots of the female plant, and consist in some samples of straight, stiff, woody stems some inches long, surrounded by the upward branching flower-stalks ; in others of more succulent and much shorter shoots, 2 to 3 inches long, and of less regular form. In either case, the shoots have a compressed and glutinous appearance, are very brittle, and of a brownish-green hue. In odour and in the absence of taste gunja resembles bhang. It is said that after the leaves which constitute bhang have been gathered little shoots sprout from the stem, and that these picked off and dried form what is called Ganja. 3. Charras. No account of hemp as a drug would be complete without some notice of this substance, which is regarded as of great importance by Asiatic nations. Charas or Churrus is the resin which exudes in minute drops from the yellow glands, with which the plant is provided in increasing number according to the elevated temperature (and altitude ?) of the country where it grows. The varieties of hemp richest in resin, at least in the Laos country in the Malayan Peninsula, scarcely attain the height of 3 feet, and show densely curled leaves. Charas is collected in several ways:— one is by rubbing the tops of the plants in the hands when the seeds are ripe, and scraping from the |

fingers the adhering resin. Another is thus performed:—men clothed in leather garments walk about among growing hemp, in doing which the resin of the plant attaches itself to the leather, whence it is from time to time scraped off. A third method consists in collecting, with many precautions to avoid its poisonous effects, the dust which is caused when heaps of dry bhang are stirred about. By whichever of these processes obtained, charas is of necessity a foul and crude drug, the use of which is properly excluded from civilized medicine. As before remarked it is not obtainable from hemp grown indiscriminately in any situation even in India, but is only to be got from plants produced at a certain elevation on the hills. The best charas, which is that brought from Yarkand, is a brown, earthy-looking substance, forming compact yet friable, irregular masses of considerable size. Examined under a strong pocket lens, it appears to be made up of minute, transparent grains of brown resin, agglutinated with short hairs of the plant. It has a hemp-like odour, with but little taste even in alcoholic solution. A second and a third quality of Yarkand charas represent the substance in a less pure state. Charas viewed under the microscope exhibits a crystalline structure, due to inorganic matter. It yields from 1/4 to 1/2 of its weight of an amorphous resin, which is readily dissolved by bisulphide of carbon or spirit of wine. The resin does not redden litmus, nor is it soluble in caustic potash. It has a dark brown colour, which we have not succeeded in removing by animal charcoal. The residual part of charas yields to water a little chloride of sodium, and consists in large proportion of carbonate of calcium and peroxide of iron. These results have been obtained in examining samples from Yarkand. Other specimens which we have also examined, have the aspect of a compact dark resin. (Pharmacographia, Fluckiger & Hanbury, 1879) |

Traditional Indian Confections and Preparations

|

1. ‘Sidhee, Subjee and Bhang (synonymous) are used with water as a drink which is thus prepared: About three tolas weight (540 troy grains) [of powdered leaf] are well washed with cold water, then rubbed to powder, mixed with black pepper, cucumber and melon seeds, sugar, half a pint of milk and an equal quantity of water. This is considered sufficient to intoxicate an habituated person. Half the quantity is enough for a novice. This composition is chiefly used by the Mahomedans of the better classes 2. The same quantity of Siddhi is washed and ground, mixed with black pepper, and a quart of cold water added. This is drank at one sitting. This is the favourite beverage of the Hindus who practice this vice, especially the Birjobassies and many of the Rajpootana soldiery. 3. The Majoon or hemp confection, is a compound of sugar, butter, flour, milk, and siddhi or bhang. The process has been repeatedly performed before us by Ameer, the proprietor of a celebrated place of resort for hemp devotees in Calcutta and who is considered the best artist in his profession. Four ounces of siddhi and an equal quantity of ghee are placed in an earthen or well-tinned vessel, a pint of water added, and the whole warmed over a charcoal fire. The mixture is constantly stirred until the water all boils away, which is known by the crackling noise of the melted butter on the sides of the vessel; The mixture is then removed from the fire, squeezed through cloth while hot, by which an oleaginous solution of the active principles and colouring matter of the hemp is obtained ; and the leaves, fibres, etc., remaining on the cloth are thrown away. The green oily solution soon concretes into a buttery mass and is then well washed by the hand with soft water, so long |

as the water becomes coloured. The colouring matter and an extractive substance are thus removed and a very pale green mass, of the consistence of simple ointment, remains. The washings are thrown away; Ameer says that these are intoxicating, and produce constriction of the throat, great pain and very disagreeable and dangerous symptoms. “The operator then takes two pounds of sugar, and adding a little water, places it in a pipkin over the fire. When the sugar dissolves and froths, two ounces of milk are added; a thick scum rises and is removed; more milk and a little water are added from time to time, and the boiling continued about an hour, the solution being carefully stirred until it becomes an adhesive clear syrup, ready to solidify on a cold surface; four ounces of tyre (new milk dried before the sun) in fine powder are now stirred in, and lastly the prepared butter of hemp is introduced, brisk stirring being continued for a few minutes. A few drops of attar of roses are then quickly sprinkled in, and the mixture poured from the pipkin on a flat cold dish or slab. The mass concretes immediately into a thick cake, which is divided into small lozenge shaped pieces. A seer thus prepared sells for four rupees. One drachm by weight will intoxicate a beginner; three drachms, one experienced in its use. The taste is sweet and the odour very agreeable. Ameer states that sometimes by special order of customers he introduces stramonium seeds, but never nux vomica; that all classes of persons including the lower Portugese or Kala Feringhees and especially their females, consume the drug; that it is most fascinating in its effects, producing extatic happiness, a persuasion of high rank, a sensation of flying, voracious appetite and intense aphrodisiac desire’. (Materia Medica of the Hindus, Dutt, 1877) |

|

‘Hemp has been propagated on account of its textile fibre and oily seeds from a remote period. The ancient Chinese herbal called Rh-ya, written about the 5th century B.C, notices the fact that the hemp plant is of two kinds, the one producing seeds, the other flowers only. In Susruta, Charaka and other early works on Hindu medicine, hemp (B’hanga) is mentioned as a remedy. Herodotus states that hemp grows in Scythia both wild and cultivated, and that the Thracians made garments from it which can hardly be distinguished from linen. He also describes how the Scythians expose themselves as in a bath to the vapour of the seeds thrown on hot coals. The Greeks and Romans appear to have been unacquainted with the medicinal powers of hemp, unless indeed the care-destroying [?] should, as Royle has supposed, be referred to this plant. According to Stanislas Julien, anaesthetic powers were ascribed by the Chinese to preparations of hemp as early as the commencement of the 3rd century. The employment of hemp both medical and dietetic appears to have spread slowly through India and Persia to the Arabians, amongst whom the plant was used in the early middle ages. The famous heretical sect of Mahomedans, whose murderous deeds struck terror into the hearts of the Crusaders during the |

11th and 12th centuries, derived their name of Hashishin, or, as it is commonly written, assassins, from hashish the Arabic for hemp, which in certain of their rites they used as an intoxicant. In 1286 of our era, the Sultan of Egypt, Bibars al Bondokdary, prohibited the sale of hashish, the monopoly of which had been leased before. The use of hemp (bhang) in India was particularly noticed by Garcia de Orta (1563), and the plant was subsequently figured by Rheede, who described the drug as largely used on the Malabar coast. It would seem about this time to have been imported into Europe, at least occasionally, for Berlu in his Treasury of Drugs, 1690, describes it as coming from Bantam in the East Indies, and “of an infatuating quality and pernicious use.” It was Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt that was the means of again calling attention to the peculiar properties of hemp, by the accounts of De Sacy (1809) and Rouger (1810). But the introduction of the Indian drug into European medicine is of still more recent date, and is chiefly due to the experiments made in Calcutta by O’Shaughnessy in 1838-39.’ Although the astonishing effects produced in India by the administration of preparations of hemp are seldom witnessed in the cooler climate of Britain, the powers of the drug are sufficiently manifest to give it an established place in the pharmacopoeia’. |

From Pharmacographia Indica, Dymock, 1893:

|

‘The hemp plant, in Sanskrit Bhanga and Indrasana, “Indra’s hemp,” has been known in the East as a fibre plant from prehistoric times. It is mentioned along with the Vedic plant Janjida, which has magic and medicinal properties, and which is described in the Athavaveda (ix., 34, 35) as a protector, and is supplicated to protect all animals and properties. The gods are said to have three times created this herb (oshadhi). Indra has given it a thousand eyes, and conferred on it the property of driving away all diseases and killing all monsters; it is praised as the best of remedies, and is worn as a precious talisman; along with hemp it prevents wandering (vishkandha), fever and the evil eye. De Gubernatis says that in Sicily the peasant women still believe in hemp as an infallible means of attaching their sweethearts. On Good Friday they take a thread of hemp and twenty-five needlefuls of coloured silk, and at midnight weave them together, repeating the following lines:— Chistu e cannavu di Christu Servi pi attaccari a chistu. “This is the hemp of Christ; it serves to attach this man.” They then enter the Church with the thread in their hands, and at the moment of the consecration of the host, they make three knots in it, adding at the same time some hairs of the man they are in love with, and invoke all the demons to attract him to his sweetheart. (Cf. Mattia ‘di Martino, Usi e credenze popolari Siciliane, Woto, 1874.) Burns in “Halloween” notices a closely-allied superstition. The intoxicating properties which the plant possesses in its Eastern home appear not to have been discovered until a more recent date, but in the fifth chapter of Menu, Brahmins are prohibited from using it, and in the sacred books of the Parsis the use of Bana for the purpose of procuring abortion is forbidden. In Hindu mythology the hemp plant is said to have sprung from the amrita produced whilst the gods were churning the ocean with Mount Mandara. It is called in Sanskrit Vijaya, “giving success,” and the favourite drink of Indra is said to be prepared from it. On festive occasions, in most parts of India, large quantifies are consumed by almost all classes of Hindus. The Brahmins sell Sherbet prepared with Bhang at the temples, and religious mendicants collect together and smoke Ganja. Shops for the sale of preparations of hemp are to be found in every town, and are much resorted to by the idle and vicious. Hemp is also used medicinally; in the Raja Nirghanta its synonyms are Urjaya and Jaya, names which mean promoter of success, Chapala “the cause of a reeling gait,” Ananda “the laughter moving,” Harshini “the exciter of sexual desire”; among other synonyms are Kashmiri “coming from Kashmir,” Matulani “the maternal uncle’s wife,” Mohini “fascinating,” &c. Its effects on man are described as excitant, heating, astringent; it destroys phlegm, expels flatulence, induces costiveness, sharpens the memory, excites appetite, &c. Susruta recommends the use of Bhang to people suffering from catarrh. In the Rajavalabha, a recent work in use in Bengal, we are informed that the gods through compassion on the human race sent hemp, so that mankind by using it might attain delight, lose fear, and have sexual desires. The seductive influences of hemp have led to the most extra vagant praise of the drug in the popular languages of India, but in truth it is one of the curses of the country; if its use is persisted in, it leads to indigestion, wasting of the body, cough, melancholy, impotence and dropsy. After a time its votary becomes an outcaste from society, and his career terminates in crime, insanity, or idiotcy. Ganja pie gur-gyan ghate, aur ghate tan andar ka, Khokat, khokat dam nikse, mukh dekho jaisa bandar ka. Who ganja smoke do knowledge lack, the heart burns constantly, The breath with coughing goes, the face as monkey’s pale you see. Fallon. According to tradition, the use of hemp as an intoxicant was first made known in Persia by Birarslan, an Indian pilgrim, in the reign of Khusru the first (A.D. 531— 579), but, as we have already stated, its injurious properties appear to have been known long before that date. There can be no doubt that the use of hemp as an intoxicant was encouraged by the Ismailians in the 8th century, as its effects tended to assist their followers in realising the tenets of the sect:— We’ve quaffed the emerald cup, the mystery we know, Who’d dream so weak a plant such mighty power could show! Hasan Sabah, their celebrated chief, in the 11th century notoriously made use of it to urge them on to the commission of deeds of daring and violence so that they became known as the Hashshashin or “Assassins.” Hasan studied the tenets of his sect in retirement at Nishapur, doubtless at the monastery noticed by O’Shaughnessy [Bengal Dispensatory), in the following terms :–“Haidar lived in rigid privation on a mountain between Nishapur and Rama, where he established a monastery; after having lived ten years in this retreat, he one day returned from a stroll in the neighbourhood with an air of joy and gaiety; on being questioned, he stated that, struck by the appearance of a plant,he had gathered and eaten its leaves. He then led his companions to the spot, who all ate and were similarly excited. A tincture of the hemp leaf in wine or spirit seems to have been the favourite formula in which Sheikh Haidar indulged himself. An Arab poet sings of Haidar’s emerald cup, an evident allusion to the rich green colour of the tincture. The Sheik survived the discovery ten years, and subsisted chiefly on this herb, and on his death his disciples at his desire planted it in an arbour round his tomb. From this saintly sepulchre the knowledge of the effects of hemp is stated to have spread into Khorasan. In Chaldea it was unknown until 728 A.H., the kings of Ormus and Bahrein then introduced it into Chaldea, Syria, Egypt and Turkey.” Taki-ed-din Ahmad, commonly known as Makrizi, who wrote a number of treatises upon Egypt in the 14th century, mentions the lease of the monopoly for the sale of Hashish in that country, and its abolition in (1286) by the Sultan. Haji Zein in the Ikhtiarat (1368), after noticing the two kinds of Kinnab mentioned by the Greeks, states that Indian hemp is known as Bang or Sabz in Shiraz; after describing its properties, he says that in cases of poisoning by it vomiting should be induced by the administration of butter and hot water to empty the stomach, and that afterwards acid drinks should be administered. The Greeks were acquainted with hemp more than 2000 years ago; Herodotus (iv., 74, 75 ) mentions it as being cultivated by the Scythians, who used its fiber for making their garments, and the seeds to medicate vapour baths. Dioscorides mentions two kinds of Kannabiis, the wild and the cultivated; the former is the Althaea cannabina of Linneus, and the latter Cannabis sativa; he states that the seeds, if eaten too freely, destroy the virile powers, and that the juice is used to relieve earache. Galen and the early Arabian physicians, such as Ibn Sina and Razi, follow Dioscorides in his opinion of the properties of hemp, and do not notice its having any intoxicating properties, and unless the Gelotophyllis of Pliny (24, 102) was Indian hemp, there is no evidence to show that the ancients were acquainted with them. Pliny says:—”The Gelotophyllis (laughing leaf) is a plant found in Bactriana, and on the banks of the Borysthenes. Taken internally with myrrh and wine, all sorts of visionary forms present themselves, and excite the most immoderate laughter, which can only be put an end to by taking kernels of the pine nut, with pepper and honey, in palm wine.” The earliest Western medical writer who distinctly mentions the intoxicating properties of hemp is Ibn Baitar, a native of Africa, who died in Damascus in 1248. All the later Mahometan physicians describe the two kinds of Kinnab mentioned by the ancients, whom they quote, and a third kind called Hindi or Indian. The name Cannabis is derived from the Persian Kanab. which is connate to the Sanskrit S’ana, the Russian Kanopla, the Irish Canaib, the Iceland Hanp, the Saxon Haenep, and the old German Hanaf. The author of the Makhzan-el-Adtriya gives Udifarunas as the Yunani name, and Kanabira as the Syrian, and also mentions a number of cant terms which are applied to it, such as Wark-cl- khyal, Hashish, Hashishat-el-fukara, Arsh-numd, Chatr-i-akh- zar, &c. Charas is described, and the practice of smoking it. The Bengal-grown hemp is said to be less intoxicating than that grown in more Northern climates. Hemp seed is called in Persian Shahdanah, “royal seeds.” The leaves are made into Sherbet and conserves for intoxicating purposes. The properties of hemp are described as cold and dry in the third degree, that is, stimulant and sedative, imparting at first a gentle reviving heat, and then a refrigerant effect, the drug at first exhilarates, improves the complexion, excites the imagination, increases the appetite, and acts as an aphrodisiac ; afterwards its sedative effects are observed— if its use is persisted in, it leads to indigestion, wasting of the body, melancholy, impotence and dropsy. Mirza Abdul Razzak considers hemp to be a powerful exciter of the flow of bile, and relates cases of its efficacy in restoring appetite, of its utility as an external application as a poultice with milk in relieving haemorrhoids, and internally in gonorrhoea, to the extent of a quarter drachm of bhang. Charas is only mentioned in comparatively recent medical works. The word is said to be derived from the Sanskrik (for) a skin, but it occurs in Persian with the primary signification of a piece of leather or cloth, the four corners of which are tied up so as to form a wallet, such as beggars carry; in Hindi it signifies a leather bag for holding water, &c. The Charas collected in Central Asia is stored in leathern bags by the cultivators. Among European writers in the East, Rheede and Rumphius figure and describe the Indian |

plant; the latter states that the kind of mental excitement it produces depends upon the temperament of the consumer. He quotes a passage from Galen, lib. I. (de aliment, facult.), in which it is asserted that in that great writer’s time it was customary to give hempseed to the guests at banquets, as a promoter of hilarity and enjoyment (the seeds are still roasted and eaten in the East). Rumphius adds, that the Mahometans in his neighbourhood frequently sought for the male plant from his garden, to be given to persons afflicted with virulent gonorrhoea or with asthma, and the affection which is popularly called “stitches in the side.” He tells us, moreover, that the powdered leaves check diarrhoea, are stomachic, cure the malady named Pitao, and moderate excessive secretion of bile. He mentions the use of hemp smoke as an enema in strangulated hernia, and of the leaves as an antidote to poisoning by orpiment. In the Bulletin de Pharnacie (1810, p. 400), we find it briefly described by M. Rouyer, apothecary to Napoleon, and member of the Egyptian Scientific Commission, in a paper on the popular remedies of Egypt. “With the leaves and tops, he tells us, collected before ripening, the Egyptians prepare a conserve, which serves as the base of the berch, the diasmouk, and the bernaouy. Hemp leaves reduced to powder and incorporated with honey, or stirred with water, constitute the berch of the poor classes. Ainslie notices Majun, a confection made with hemp leaves to be used as a sweetmeat, the composition of which varies in different parts of the East, and to which are often added other intoxicating drugs. O’Shaughnessy in the Bengal Dispensatory 1842 gives a detailed account of its preparation in Calcutta. The medicinal properties of Cannabis have now been investigated by many European physicians in India. O’Shaughnessy tried it with more or less success in various diseases, especially in tetanus, hydrophobia, rheumatism, the convulsions of children and cholera. Subsequent experience has confirmed the value of the drug as a remedy in tetanus and cholera. In the former disease we have obtained most satisfactory results, large doses are required, and the patient must be kept under the influence of the drug for some days. In cholera its action may be compared with that of opium ;it is most likely to be successful when resorted to early in the disease. People suffering from painful chronic diseases, such as rheumatism, are completely relieved of their pains by hemp, but as the effects of the drug go off, the pains return; some of O’Shaughnessy’s patients became cataleptic whilst under its influence. Christison, speaking of Indian Hemp, says:— “I have long been convinced, and new experience confirms the conviction, that for energy, certainty, and convenience, it is the next anodyne, hypnotic and antispasmodic, to opium and its derivatives, and often equal to it.” Among the “special opinions” collected by Dr. Watt for the Dict, of the Econ. Prod, of India, we observe that Dr. S. J. Ronnie recommends the tincture in doses of from 15 to 20 minims three times a day in acute dysentery, and states that he, as well as other medical officers, obtained excellent results with it. Dr. J. E. T. Aitchison states that the oil of the seeds, known as Kandir yak in Turkistan, is used in Kashmir as a liniment for rheumatic pains. Others notice it as having valuable narcotic, diuretic and cholagogue properties. (Op. cit., vol. ii., p. 124.) A. Aaronson states in the British Journal of Dental Science, that the tincture as a local anaesthetic is perfectly satisfactory. He has extracted with its aid as many as twenty-two teeth and stumps at one sitting. His plan is to dilute the tincture some three or five times, according to the probable duration of the operation. The diluted tincture is then applied on cotton wool to cavities, if such exist, and also about the gums of the affected teeth. The beaks of the extracting forceps are also, after being warmed, dipped in the tincture. In cold weather it is best to dilute the tincture with warm water. His patients acknowledge the immunity from pain they enjoyed during the operations, and all expressed surprise and pleasure at the simplicity of the performance. Tannate of cannabin has recently been recommended as a hypnotic. Cannabis appears capable, directly or indirectly, of causing uterine contraction, as in many cases of uterine haemorrhage ; and it is also said to provoke this act during labour with as much energy as ergot, but with less persistent action. A recent correspondence in the Lancet, anent the variation in action and occasional toxic effects of this drug, has brought from Dr. J. Russell Reynolds an important contribution respecting its clinical value. In explaining the occasional toxic effects of this drug, Dr. Reynolds says two things must be remembered: first, that, by its nature and the forms of its administration, cannabis indica is subject to great variations in strength. Extracts and tinctures cannot be made uniform, because the hemp grown at different seasons and in different places. varies in the amount of the active therapeutic principle. It should always be obtained from the same source, and the minimum dose should be given at first, and gradually and cautiously increased. The second important fact to keep in view is, that individuals differ widely in their relations to various medicines and articles of diet— perhaps to none more than to substances of vegetable origin, such as tea, coffee, ipecacuanha, digitalis, nux vomica, and the like. In addition to the purity of the drug, the possibility of idiosyncrasy must be borne in mind as calling for caution in giving Indian hemp. By gradually increasing the dose and habituating the organism to its use, the use of cannabis indica may be pushed to 3 or 4 grains of the extract at a dose with positive advantage. But in Dr. Reynolds’ experience 1 grain would bring about toxic effects in the majority of healthy adults; and 1/4 of a grain has done the same, but never 1/5, which is the proper amount with which to begin the use of the drug among grown persons, of a grain being the proper initial dose for children. The best preparation for administration is the tincture— 1 grain to 20 or 10 minims—dropped on sugar or bread. The minimum dose should be given, as before stated, repeated every four or six hours and gradually increased every third or fourth day, until either relief is obtained or the drug is proved useless. With such precautions, Dr. Reynolds states he has never met with toxic effects, and rarely failed to ascertain in a short space of time the value or uselessness of the drug. Its most important results are to be found in the mental sphere; as, for instance, in Senile Insomnia, with wandering. An elderly person (perhaps with brain softening), is fidgety at night, goes to bed, gets up (thinks he has some appointment to keep, that he must dress and go out. Day, with its stimuli and real occupations, finds him quite rational again. Nothing can compare in utility to a moderate dose of Indian hemp at bedtime—1/4 to 1/3 of a grain of the extract. In alcoholic subjects it is uncertain and rarely useful. In Melancholia it is sometimes serviceable in converting depression into exaltation; but unless the case has merged into senile degeneration, Dr. Reynolds does not now employ cannabis indica. It is worse than useless in any form of mania. In the occasional night restlessness of general paretics and of sufferers from the “temper disease” of Marshall Hall, whether children or adults, it has proved eminently useful. In painful affections, such as Neuralgia, Neuritis, and Migraine, Dr. Reynolds considers hemp by far the most useful of drugs, even when the disease is of years’ duration. In neuritis the remedy is useful only in conjunction with other treatment, and is a most valuable adjunct to mercury, iodine, or other drugs, as it is in neuralgia when given with arsenic, quinine, or iron, if either is required. Many victims of diabolical migraine have for years kept their sufferings in abeyance by taking hemp at the threatening or onset of the attack. In sciatica, myodynia, gastrodynia, enteralgia, tinnitus aurium, muscse volitantes, and every kind of so-called hysterical pain, cannabis indica is without value. On the other hand, it relieves the lightning pains of Ataxia, and also the multiform miseries of the gouty, such as tingling, formication, numbness, and other paraesthesia. In clonic spasm, whether epileptoid or choreic, hemp is of great service. In the Eclampsia of children or adults, from worms, teething (the first, second, or third dentition), it gives relief by itself in many cases. Many cases of so-called Epilepsy in adults— epileptoid convulsions, due often to gross organic nerve-center lesions— are greatly helped by cannabis indica, when they are not affected by the bromides or other drugs. Take, for instance, violent convulsions in an overfed man, who is attacked during sleep a few hours after a hearty supper, the attacks recurring two or three times an hour for a day or two, in spite of “clearing the primes vice,” or using bromine or some other classic drug. These attacks may be stopped at once with a full dose of hemp. In brain tumours or other maladies in the course of which epileptoid seizures occur, followed by coma, the coma being followed by delirium,— first quiet, then violent— the delirium time after time passing into convulsions, and the whole gamut being repeated, Indian hemp will at once cut short such abnormal activities, even when all other treatment has failed. In genuine epilepsy it is of no avail. In cases where it has seemed to do good, the author doubts the correctness of the diagnosis, and suspects organic lesion or eccentric irritation. In tonic spasms, such as torticollis and writers’ cramp, in general chorea, in paralysis agitans, in trismus, tetanus, and the jerky movements of spinal sclerosis, cannabis indica has proved absolutely useless. At the same time, it is most valuable in the Nocturnal Cramps of gouty or old persons, in some cases of Spasmodic Asthma, and in simple Spasmodic Dysmenorrhoea. Thus it will be perceived that for the relief of suffering, quite apart from a curative effect, hemp must ever be held in high esteem, and ranked with the poppy and with mandragora. {Medical Annual, 1891.) |

Materia Medica of the Hindus, Dutton, 1877

|

THE Cannabis sativa has been used from a very remote period both in medicine and as an intoxicating agent. A mythological origin has been invented for it. It is said to have been produced in the shape of nectar while the gods were churning the ocean with the mountain called Mandara. It is the favourite drink of Indra the king of gods, and is called vijayd, because it gives success to its votaries. The gods through compassion on the human race sent it to this earth so that mankind by using it habitually may attain delight, loose all fear, and have their sexual desires excited. On the last day of the Durga pooja, after the idols are thrown into water, it is customary for the Hindus to see their friends and relatives and embrace them. After this ceremony is over it is incumbent on the owner of the house to offer to his visitors a cup of bhang and sweet-meats for tiffin. An intoxicating agent with such recommendations cannot but be popular and so we find it in general use amongst all classes especially in the North-West provinces and Behar. In Bengal it has latterly become the fashion to substitute brandy, but I well remember having seen in the days of my boyhood the free use of bhang among the better classes of people who would have shunned as a pariah any one of their society addicted to the use of the forbidden spirituous liquor. At the doors of many rich baboos, Hindustani durwans could be seen rubbing the bhang in a stone mortar with a long wooden pestle, and the paste so prepared was not solely intended for the use of the servants. I do not mean to say that all classes of Hindoos without exception are or were addicted to the use of bhang. Some castes among the up-country men and some classes of people amongst Bengalis are as a rule very temperate in their habits and do not use any narcotic at all; but the ordinary run of orthodox Hindus, accustomed to have their little excitements, use bhang for the purpose without incurring any opprobium such as would result from the use of spirituous liquors. The three principal forms in which Indian hemp is met with in India are, 1, Ganja, the dried flowering tops of the female plant, from which the resin has not been removed. 2, Charas, the resinous exudation from the leaves, stems and flowers. 3, Bhang, the larger leaves and seed vessels without the stalks. Sir William O’Shaughnessy has so well described the prepara- tions of Indian hemp in use amongst the natives, and his name is so intimately associated with the history of this drug, that I cannot do better than quote his account of them. “Sidhee, Subjee Bhang (synonymous) are used with water as a drink which is thus prepared: About three tolas weight (540 troy grains) are well washed with cold water, then rubbed to powder, mixed with black pepper, cucumber and melon seeds, sugar, half a pint of milk and an equal quantity of water. This is considered sufficient to intoxicate an habituated person. Half the quantity is enough for a novice. This composition is chiefly used by the Mahomedans of the better classes. “Another recipe is as follows: The same quantity of Siddhi is washed and ground, mixed with black pepper, and a quart of cold water added. This is drank at one sitting. This is the favourite beverage of the Hindus who practice this vice, especially the Birjobassies and many of the Rajpootana soldiery. ” From either of these beverages intoxication will ensue in half an hour. Almost invariably the inebriation is of the most cheerful kind, causing the person to sing and dance, to eat food with great relish, and to seek aphrodisiac enjoyments. In persons of a quarrelsome disposition it occasions, as might be expected, an exasperation of their natural tendency. The intoxication lasts about three hours, when sleep supervenes. No nausea or sickness of stomach |

succeeds, nor are the bowels at all affected; next day there is slight giddiness and vascularity of the eyes, but no other symptom worth recording. “Ganja is used for smoking alone: one rupee weight (180 grains) and a little dried tobacco are rubbed together in the palm of the hand, with a few drops of water. This suffices for three persons. A little tobacco is placed in the pipe first, then a layer of the prepared ganja, then more tobacco and the fire above all. Four or five persons usually join in this debauch. The hookah is passed round, and each person takes a single draught. Intoxication ensues almost instantly and from one draught to the unaccustomed; within half an hour, and after four or five inspirations to those more practised in the vice. The effects differ from those occasioned by the siddhi. Heaviness, laziness, and agreeable reveries ensue, but the person can be readily roused and is able to discharge routine occupations, such as pulling the pankah, waiting at table, etc. “The Majoon or hemp confection, is a compound of sugar, butter, flour, milk, and siddhi or bhang. The process has been repeatedly performed before us by Ameer, the proprietor of a celebrated place of resort for hemp devotees in Calcutta and who is considered the best artist in his profession. Four ounces of siddhi and an equal quantity of ghee are placed in an earthen or well-tinned vessel, a pint of water added, and the whole warmed over a charcoal fire. The mixture is constantly stirred until the water all boils away, which is known by the crackling noise of the melted butter on the sides of the vessel; The mixture is then removed from the fire, squeezed through cloth while hot, by which an oleaginous solution of the active principles and colouring matter of the hemp is obtained ; and the leaves, fibres, etc., remaining on the cloth are thrown away. The green oily solution soon concretes into a buttery mass and is then well washed by the hand with soft water, so long as the water becomes coloured. The colouring matter and an extractive substance are thus removed and a very pale green mass, of the consistence of simple ointment, remains. The washings are thrown away ; Ameer says that these are intoxicating, and produce constriction of the throat, great pain and very disagreeable and dangerous symptoms. “The operator then takes two pounds of sugar, and adding a little water, places it in a pipkin over the fire. When the sugar dissolves and froths, two ounces of milk are added ; a thick scum rises and is removed ; more milk and a little water are added from time to time, and the boiling continued about an hour, the solution being carefully stirred until it becomes an adhesive clear syrup, ready to solidify on a cold surface ; four ounces of tyre (new milk dried before the sun) in fine powder are now stirred in, and lastly the prepared butter of hemp is introduced, brisk stirring being continued for a few minutes. A few drops of attar of roses are then quickly sprinkled in, and the mixture poured from the pipkin on a flat cold dish or slab. The mass concretes immediately into a thick cake, which is divided into small lozenge shaped pieces. A seer thus prepared sells for four rupees. One drachm by weight will intoxicate a beginner; three drachms, one experienced in its use. The taste is sweet and the odour very agreeable. Ameer states that sometimes by special order of customers he introduces stramonium seeds, but never nux vomica; that all classes of persons including the lower Portugese or Kala Feringhees and especially their females, consume the drug; that it is most fascinating in its effects, producing extatic happiness, a persuasion of high rank, a sensation of flying, voracious appetite and intense aphrodisiac desire.”* The leaves of Cannabis sativa are purified by being boiled in milk before use. They are regarded as heating, digestive, astringent, and narcotic. The intoxication produced by bhang is said to be of a pleasant description and to promote talkativeness. |